Destination thriller set in THAILAND (and London)

Novel set in Zurich (plus author Question and Answer)

17th March 2015

Hausfrau by Jill Alexander Essbaum, novel set in Zurich.

“Pain is the proof of life”

“Pain is the proof of life”

A novel that is as sharp, sparkling and multi faceted as a diamond, and as glistening as the glittering peaks of the Swiss Alps, it is incisive as it is “Glacier carved”.

Anna Benz, an American, is married to Bruno and lives with him in Dietlikon, Zurich. To all intents and purposes they have the trappings of a well-to-do banking family in a suburb of this desirable city. They have three children – Charles, Viktor and Polly Jean, and mother-in-law Ursula, is waiting in the wings just down the road, ready to babysit at the drop of a resentful hat.

Anna is having analysis with the Jungian, Dr Messerli, with whom she has sessions exploring the nature of therapy, neurosis and the meaning of life. They talk about some aspects of Anna’s life and Anna brings her dreams for interpretation. Dr Messerli is a sympathetic analyst but there is not really much engagement from either side. They discuss how Anna can steer herself into trajectories that force her “to participate more fully with the world“. And that is the fundamental issue for Anna, she is like an observer of her own life, with compulsions and predilections that drive her into situations that incur dire consequences.

Anna is emotionally hollow, disengaged from life, and in her search to be cosseted, she is driven to find connections through sexual encounters. She sleepwalks into relations with multiple partners, searching for what? Closeness, bonding, love? It is not sexual addiction, she is more like a blind puppy nuzzling for someone to enable her to engage with her otherwise grey life. Her husband has a tendency towards curt and sometimes aggressive outbursts, which further consolidate her precarious grip on propriety and reality. She has no sense of self and is like a willing pawn in the sexual dance, over which she seems to have little control. Whilst she looks to others to give her meaning, she slides further down the black hole of life – a life in a foreign country where the people, the customs and the language are all alien and cold, and all serve to perpetuate her role as outsider. “The Alps are the door I am locked behind“, she ruminates.

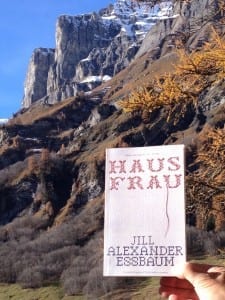

Our Advance Reader Copy in the Alps

The author is exceptionally skilled with words and she clearly delights in word play. And that is one of the many pleasures of the book. Whether it is her playing around with German words, musing on the “rapid, scuttling Schwizerdütsch” (Swiss German) or pondering the proximity of homophones like Bern and burn, succeed with secede, it is all deftly tackled.

Zurich Main Station

This is indeed one woman’s journey through married life, but there are multiple layers that feed into her story and which add fabulously contoured dimensions. Anna attends German classes at the Migros Klubschule. The German language serves as a base for Schwizerdütsch, and the play on words and their double edged meaning are a wonderful construct. Dr Messerli is sharp, as sharp as a knife in her observations, and her name ironically means little knife in Swiss German. One of Anna’s amorati is Stephen Nicodemus, whose surname is found in the Bible, a devotee of Christ; there is much debate about personal determination and the nature of the devil/religion in some of the moral questions that arise.

Anna Karenina, Emma Bovary and now Anna Benz (coincidence that she takes her initials from her forebears? I think not).

Zurich is a character in its own right and serves like a cocoon to the story. Towards the end of the book, Anna walks across the innumerable bridges that straddle the river in the city, she spends a lot of time at the Hauptbahnhof (see our photos above); at one point the family takes the boat across the Zürichsee; she shops in Migros, the supermarket with ubiquitous outlets (to the strains of 80s euro muzak on a loop)…. The tremendous sense of location anchors the story in a very Swiss setting, so anyone who knows the country will recognise the acute observations and will be able to look in on Anna’s story with empathy and familiarity.

You will discover what “Was fuer ae huere Schweinerei” means in the book but you will never want to use the phrase if you visit Switzerland. Enjoy this extraordinary literary page-turner!

Tina for the TripFiction Team – and now I hand over to Jill who has very kindly agreed to answer our questions:

TF You really manage to convey Anna’s dislocation, both emotionally and physically. What was your inspiration for the story?

JAE In some ways the story is an homage— not a retelling— to Madame Bovary. In two ways actually.

The first is clear, I hope: Anna, like Emma, is a woman who is out-of-place in her environment. Alien, reckless—but not altogether unfeeling nor unworthy of love (as if anyone truly is). And yet… That’s a loaded ‘yet’. The second nod I hope comes in the form of language. I worked hard to ‘mot juste’ this novel (if I can turn that as a verb) in order that Anna’s nebulous, imprecise selfhood might be precisely described. To concretize her abstractness.

TF I wonder if you have a backstory for Anna – in other words, why might she have chosen (consciously and unconsciously) to marry Bruno.? What happened in her earlier years that might have affected her so profoundly, causing her to act as she does?

JAE I’ve thought about this and here’s what I’ve come up with: . Think about it— Anna hardly ever tips her hand. When does she open up? Even at the end of the novel when she’s ready to (and it’s only in the final act that she’s ready to), her husband prevents it. She can’t even tell her analyst the whole truth. As far as her marriage, Bruno might have been the only kind of husband she could have managed— rather, the only kind who could manage her. A woman who can’t make clear decisions requires a man who can. And really, in the end, there’s something heroic about him (that one particular instance aside). He’s bought into Anna. He’s no fool. Not a true cuckold.

TF In many ways, this is quite a serious portrayal of mental health. Seemingly Anna functions perfectly well within society, yet she cannot really find help. Please tell us a little more about your thoughts.

JAE Anna’s not ill. Anna’s broken. As in, she came from the factory already damaged. How I’ve always thought of her is this: she is an entirely failed person. I mean that in a very specific way. Doktor Messerli addresses this in a speech not too far into the book, confronting Anna and asking her if she wants to succeed in her life. And by success, she doesn’t mean achieve goals and rack up accomplishments. It’s a far more nuanced sort of triumph. Anna can’t wrap her head around it. It’s a flummoxing question. So I don’t know that I’d call what she experiences mental illness. Psychic illness? Spiritual illness? You bet. And it festers. And worsens. And feeds on itself.

TF The story is set in Switzerland. You clearly know the country really well, you portray it ‘warts and all’. Tell us a little more about your experience there.

JAE I lived there for just over two years. Bluntly? I was miserable. But it was a complicated misery mitigated by at least a dozen factors. Chief among them, however, was the fact that once there, I had nothing to do with my hands. Which is to say I didn’t have much of a reason to be there except to support my then-husband who was enrolled in the International School of Analytic Psychology where he studied Jungian analysis. I didn’t have a job. I had only a couple of friends. Days yawned before me and I wandered the aisles of the grocery store and rode the trains and hobbled around in the woods and climbed the hill behind our little house to sit on the bench and have a think or have a cry. Sound familiar? I had no context of my own. My German was shoddy and by nature I’m generally skittish and I found it difficult to interact with strangers. So I sat back and watched. People. Places. The sky. I wrote a lot of poetry. I traveled a bit. But as the song says, I was so lonesome I could cry. And I did. My husband couldn’t really solve this for me. Loneliness is an existential issue. And of course it goes beyond being physically alone. So there was that.

But like Anna, the particular habits of wifery really did bring me comfort and a measure of joy. I chased those comforts.

TF What were the things you most/least enjoyed about the country?

JAE Most: The trains; the woods behind Dietlikon (oh yes, I too lived in Dietlikon); Lindt chocolate; wandering around the shops underneath the Hauptbahnhof; the Bröckihaus (resale shop) just on the north side of the Hauptbahnhof; the dairy products that tasted as if just that morning they’d been in the cow; sitting at the edge of the lake and watching the waters; the Lutheran Church in Zürich; (now don’t laugh…) the scent of dirt and manure when the farmers fertilized the fields— just so natural and… correct and true… it smelled as if all was right with the world, you know?; and the landscape, which I love. Still. And always.

Least: The rigidity— you must tie your recycling in a certain way for example or it won’t be picked up; how unapproachable everyone seemed to me; the code of conduct I never quite cracked; the cost of living!

TF You clearly have a gift for playing with words and language. How have you developed that interest and how long have you been writing?

JAE While this is my debut novel, this isn’t my first published book. I’ve published several collections of poetry and up until now, I’ve been Jill Alexander Essbaum, poet. My FIRST true love was telling jokes. Jokes and poems operate in a very similar manner—they spin on an axis, are dependent on the interplay of language, etc. I teach in a masters program and I’ve come to the conclusion that ultimately I don’t have a particular love for poetry, or an allegiance to literature in general. What I’m passionate about—and fiercely, madly, foam-at-the-mouth-rabidly passionate about— really, is words. Because it’s words that make up sentences that make up stanzas or paragraphs or poems or stories. I’m most concerned with wordery. I don’t know whether that’s a legitimate word itself but I think it should be. Because poems are made with words, not concepts. I think, at least.

TF What thoughts do you have for someone who would like to write?

JAE Take the Nike advice: just do it! If it’s terrible— who cares? It won’t get any good unless you put it on paper first. I’m a huge proponent of the ‘Ass in Chair’ school of thought when it comes to writing. Show up. That’s the first rule. Keep showing up. Failing to commit is the single most common mistake I see in young (and young-to-the-craft) writers.

TF What are you working on at the moment and will location play a big part?

JAE Hm. Tricky question. I’m working on finishing a book of poems. Location? Yesssssss, but it’s more of a psychic location. How’s that for an elliptic answer? I will say however that there’s a dash of Swissitude tossed in there for good measure.

In terms of fiction… I’m still working that one out. I’ll take suggestions! I like basketball a lot. I may write a book about basketball.

TF When you travel what kinds of books do you like to read?

JAE I like biographies quite a bit and of course really good lose-yourself-in-the-plot fiction.

TF What are you reading at the moment? Tod Goldberg’s Gangsterland; Don Paterson’s The Book of Shadows, Jillian Lauren’s Some Girls, and speaking of basketball, Jack McCallum’s Dream Team. (And an occasional Archie comic book for good measure to boot!)

You can follow Jill on Twitter and Facebook

And do drop by and connect with Team TripFiction via social media: Twitter, Facebook and Pinterest and when we have some interesting photos we can often be found over on Instagram too.

Please wait...

Please wait...